AN INTERVIEW WITH GARNETTE LOCKHART

Robert Buckland interviews the

author of

Pitch Weed: The Memoir of a Working Woman

2008 winner of the Novel of

Promise Competition

Buckland: I know you haven't shown any great interest in talking about yourself, but when people read these excerpts, they're going to want to know something about the person who wrote it.

Lockhart: Fair enough. Born in Danville, Kentucky, the youngest of four. Family moved twice before I was two — to Jackson, Mississippi and then to Nashville, Tennessee. I grew up there on the campus of an historically black university.I was a National Achievement scholar. I considered journalism as a career. In the end I chucked it all to take advantage of the freedom of adulthood. Spent my early twenties in Atlanta and returned to Nashville to marry and have one son. He's now twenty-two and I've worked in the health field for twenty years.

Buckland: This is a work of historical fiction. To what extent did you feel it necessary to research its period and place?

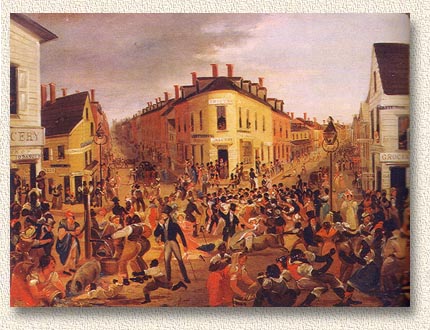

Lockhart: Since I was "urbanizing" a piece of history, I felt an obligation to base my characters in fact. The Five Points neighborhood of New York was itself very much a famous -- or infamous -- fact, of course, and the character of Nigger Joe Berlin is based on a dive owner mentioned in Luc Sante's Low Life, who sits atop a high stool and dispassionately oversees the goings-on in his gathering house for homosexuals. People visited in the hundreds, it was said.

Buckland: Interesting that some of the most squalid creatures of Pitch Weed happen also to be those with actual historical antecedents.

Lockhart: You're right. The Madame in Pitch Weed is based on the historical Madame Restell, called the "Wickedest Woman in New York".In earlier drafts, I used the Rogue's Lexicon to inform my character's language, but backed away from more than the use of "bleak'" for "pretty" or "attractive". I felt to use more historical slang would interfere with the reader's understanding.

I read a good deal about where blacks would live in New York and found them to be scattered, but most often mentioned in the deplorable conditions of Cow Bay tenements. It was during this research that I discovered the freemen's settlement of Seneca Village, which was razed for Central Park.

Buckland: How conscious is the link to contemporary society? Many writers feel obliged to ascribe serious sociological intent to their work, but was that your reason for writing the story you've written? In other words, which came first, the ripping yarn or the commentary on our times, if it is in fact one?

Lockhart: The commentary was a consistent motivator for character development. High Yella King, the narrator's son in the first chapter, is crafted as the forerunner to today's urban black male. Good or bad, he is the son of a single mother, has no contact with his father, is filled with rage and viewed by white men as possibly crazed. He is promiscuous to the extreme, violent and profane. His mother is in some ways, the sort of mother who raises serial killers.Through her life, though not completely of her making, he is made precocious with regard to sex, the exploitation of others weakness and cannot reliably be guided by her or protected by her. They literally grew up together. Again, stereotypes given three dimensions.

Buckland: Set this book for me in the context of your other writing. Is Pitch Weed the first novel you've written? If so, had you made other, earlier attempts at book-length works? Short stories or other forms?

Lockhart: Pitch Weed has some of the structure of a novel written but never completed about twenty years ago. It dealt with colorism, without the biracial element. I wrote daily for about two years in long hand on legal pads and carted them everywhere I went. Before that, my first and only short story was written in the fourth grade. And I wrote to amuse my mother -- a blues song, a poem here and there.In my early twenties, I wrote a collection of erotic poetry that I never felt was good enough for publication. Then for about twenty years, I lay fallow. No muse, until a gathering of stimuli created Lala King.

Buckland: This novel is the first of a trilogy and extends from the U.S. Civil War to the end of the nineteenth century. Have you written the other two parts? What are their periods?

Lockhart: Yes, I've thought of calling the complete work, The Chronicles of Kings. The second novel is a sequel and is narrated by the second generation of Kings and ends in 1897. The third novel picks up in 1897 and ends just prior to WWII. I'm currently in rewrites on the second novel that should significantly restructure the third. All three exist in relative completion, however. And a fourth, as well.

Buckland: Did you write the trilogy straight on, as though the three books were all part of a single work?

Lockhart: Yes. Although each was conceived through a different narrator or series of narrators.

Buckland: How carefully do you structure your storyline in advance? Do you sit down and make it up as you go along, or do you work from a detailed plan?

Lockhart: Character development informs most of the plot. Since I write daily and some might say, obsessively, I find no problem in playing around with the characters and seeing where they lead me. Pitch Weed initially had the entire story arc contained in perhaps three chapters. It was simplistic. More like a narrative that you might rattle off the top of your head. As I worked within that skeleton, I fleshed it out. I created character studies with motivations, strengths and weaknesses; I outlined and eventually created family trees. But only after I'd let the first ideas pour out. And they don't pour out with headings and bullet points.

Buckland: Many writers are influenced by writing workshops and other forums of peer criticism. Is this the case with you? Do you alter your work in response to criticism or do you keep it to yourself until it's done?

Lockhart: I try not to read fiction when I'm actively writing. And I've never attended a workshop. About a month ago, I allowed a family member to read the first chapter of Pitch Weed. Mistake. I understand now why artists choose pseudonyms. This contest was the first that I've ever pursued being edited. My style of writing is raw. I wouldn't expect an outpouring of support for it. It's not mainstream.

Buckland: A reader of the opening chapter of Pitch Weed is struck by the narrator's voice. How did you evolve this voice? Does La's speech have any historical basis? Does it owe much to other literary sources? Or is it largely imagined, based perhaps on contemporary speech?

Lockhart: I think that La sounds like southern black women have sounded and still sound in certain areas. I hear the cadence of her voice as one might a favorite song. She's familiar, but imagined.

Buckland: The characters depicted in the opening chapter are unusually vivid. To what extent are some or all of them based on persons you have known?

Lockhart:They are all parts of people that I've known. People that I've seen and never spoke to, but were struck by what I imagined them to be. I focus on the most stunning parts. I'm blessed to have known and been related to, some rather stunning individuals.

Buckland: And the title? The memoir of a working woman, yes. But what about pitch weed?

Lockhart:Pitch Weed isn't a literal botanical reference, rather a metaphor for a lot of things going on in the novel. It's reference to the literal color of the majority of the characters and it's a nod to the almost creative hate that stereotypes and dismisses them, i.e. "black as pitch", tar-baby, dinge and of course, the all-encompassing "nigger." Weed is also chaff, worthlessness,unsightliness even. But it simultaneously connotes resilience, prolific growth, being "hard to kill." In 19th century New York, we have weeds, these black weeds in the Five Points who are dismissed by society as a whole, yet are thriving, often lawlessly. As one of the characters in the book says, "You gotta take to get."

I like to think that pitch weed is also a reference to the importance that herbal medicine has for the central character, Lala King.It harkens to her upbringing in Louisiana, where voodoo conjuring relies on the same understanding of herbal medicine that she has. Last but not least, being for my purposes a fictional plant, "pitch weed" is both a wink at modern day drug use, Native American plant-based spiritual quests and a smirking take on the stereotype of the black man as smoking so-called "weed" on a regular basis.

Buckland: What's up next for Garnette Lockhart -- or are you still cooking this one?

Lockhart: Once I get the King family settled and put away, I've given thought to a contemporary novel. The fragility of black manhood is a favorite subject. I come from an athletic family. Lots of good stuff there.

Buckland: When handling the structure of such a necessarily long work as a trilogy must be, have you attempted some sort of story arc that extends across all three? Or is each effectively self-contained and only tenuously connected to the others?

Lockhart: The Kings have a secret and it's not the type of secret that goes away. They are necessarily concerned with "blood". The trilogy takes them towards a characteristically perverse solution.

Buckland: When do you write and how? On a keyboard? In longhand?

Lockhart: I write on a keyboard, most evenings after I'm settled. When I go to bed, I do so with the part of the manuscript I've worked, or with my trusty legal pad to make notes and outline.

Buckland: Are you a rigorous re-writer or does the first draft generally do the job, perhaps with a little later tinkering?

Lockhart: Rigorous is the word.

Buckland: There are an awful lot of books in the world and those are just the ones that got published. We wouldn't have chosen The Pitch Weed if we didn't think this chapter striking and deserving. But what in your own opinion should recommend the book?

Lockhart: It takes a new and not necessarily reverential view of race and sex. Degradation has many faces. Slavery is just one form of degradation. To what lengths will a people go, what are they willing to endure, when they reject the onus of de-personhood? Were there black people who considered themselves deserving of a piece of the pie, even when they weren't invited to the table? Surely. Find them in my book and realize that sometimes treachery is best met with treachery. For then, as now, the most successful students are those who take the master's lessons to heart.

THE COMPETITION RULES AND PRIZES

If you've arrived at this page from outside the Ocean Cooperative web site and don't see a menu bar to the left, click here to go to our home page and learn more about our innovative publishing model.

Robert Buckland at My office telephone number is (613) 659-3666

You can e-mail me at: words@oceancooperative.comYou can write me at: 640 Sand Bay Road, Lansdowne, Ontario, Canada K0E 1L0